Scientists armed with a new computer model have taken a step closer to unlocking the mind-bending secrets of optical illusions that trick the brain into seeing false colors when it processes images.

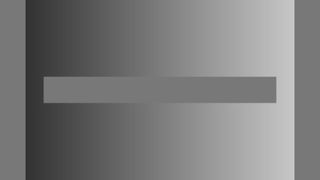

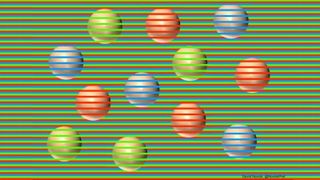

“Simultaneous contrast illusions” are a broad group of deceptive depictions that trick people into thinking that specific parts of an image are different colors from each other, but are actually the same their color. The effect depends on the illustrator changing the light or color in the background, to change our perception of the objects in the foreground. For example, in the image above, the smaller bar in the center of the image is a single gray color but appears to be a gradient of different colors because the background is lighter on one end and darker on the other. Another example is the Munker-White illusionshown in the image below, where the 12 spheres appear to be red, purple and green but are actually the same shade of beige.

Scientists have known why these illusions work for more than a century, but in all that time, experts haven’t agreed on exactly how they fool the brain. There are two possible explanations. The first is that the illusion is created from the bottom up, starting with low-level neural activity that does not require previous exposure to this type of illusion. The second is top-down, meaning it requires higher brain functions and activates what your brain has already learned about brightness and light color over time.

In a new study, published on June 15 in the journal Computational Biologya pair of researchers used a new computer model that mimics human vision to try to settle the debate once and for all.

Related: A new type of optical illusion tricks the brain into seeing a dazzling beam

The model, known as the “spatiochromatic bandwidth limited model,” uses computer code to simulate how the network of brain cells, or neurons, that first receive data from the eyes begin to decipher an image. before that data is sent to other, “higher-level” brain regions to be fully processed. The model divides the image into sections, measures the brightness of each section and then combines those assessments into a report that can be sent to the brain, similar to what happens with human vision.

The beauty of this model is that the code allows individual sections to be processed only at the same speed as human neurons can process them, thus restricting the model to match our own visual limitations, learning of co-authors. Jolyon Troscianko, a visual ecologist at the University of Exeter in the UK, told Live Science. “This aspect of the model is particularly novel – no one seems to have considered the effect that limited bandwidth can have on visual processing,” he added. Specifically, the new model takes into account how quickly neurons can “fire,” or shoot a message to other neurons in their network.

The researchers used their new model to study more than 50 simultaneous contrast illusions to see if the program mistakenly identifies specific parts of the images as different colors, as a human would. (It’s not clear how many simultaneous contrast illusions exist, but probably hundreds, the report’s authors say.)

During these experiments, the model was constantly tricked into identifying the wrong colors, Troscianko said. “My colleague [Daniel Osorio] kept emailing me new illusions, saying he didn’t think it would work on this one,” he added. “But to our surprise and delight, it generally predicted the illusion in almost all cases .”

Because the model was also “fooled” by these illusions without the equivalent complex processing power of the human brain, this suggests that higher-order visual processing or past experiences are not required for the illusions to work. this. This seems to confirm the bottom-up hypothesis which says that only the basic level of neural processing is responsible for the deception of images, the authors concluded.

“Essentially, many illusions previously thought to rely on complex visual processing, or at least visual processing that requires feedback loops, can actually be explained by something as simple as a single layer of neurons,” said Troscianko.

The results support similar findings from a 2020 study in the journal Perspective Research. In that study, children who were born with cataracts but underwent successful cataract removal were deceived by images shortly after regaining their vision, despite having no previous visual experiences to provide context for the pictures.

#brainbending #secret #hundreds #optical #illusions #finally #revealed

Add Comment